A’s say goodbye to Oakland, win last home game

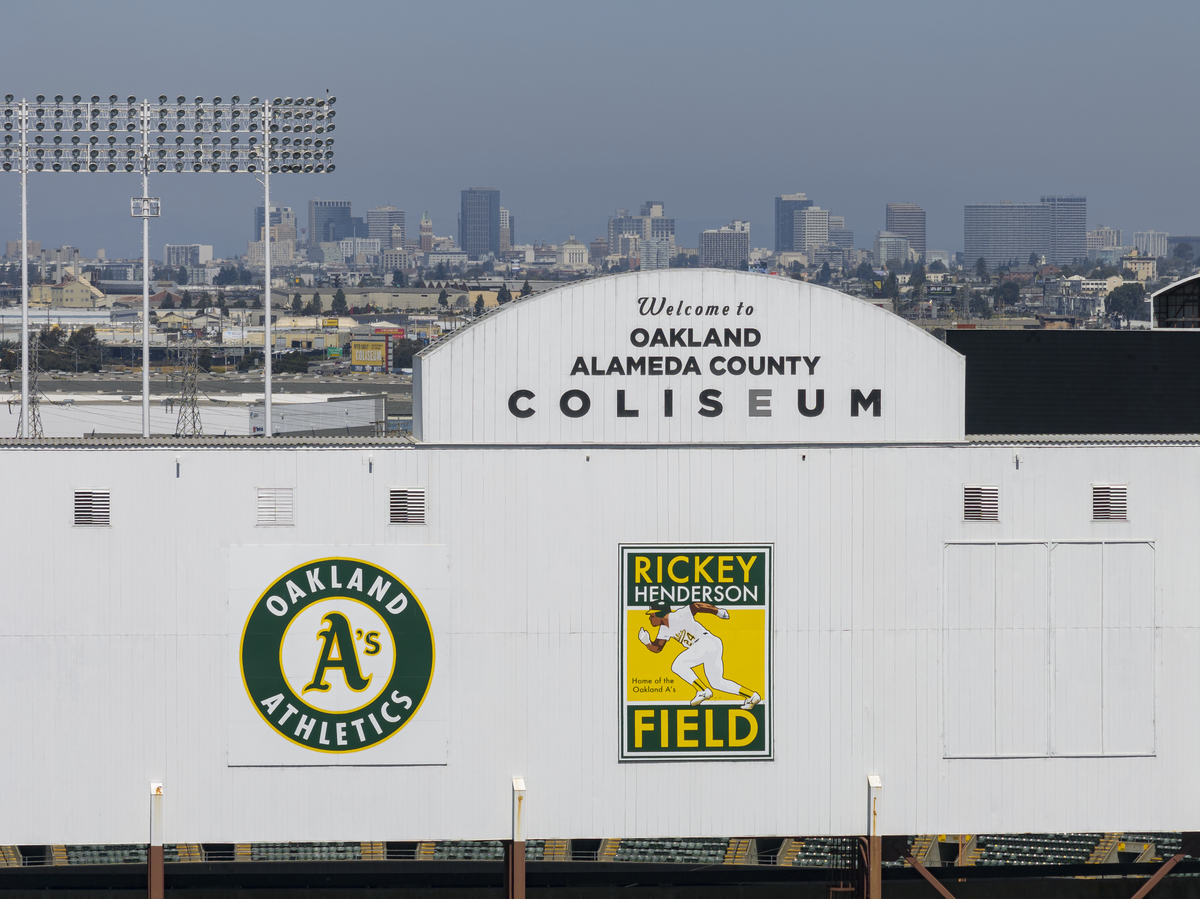

It is the end of an era for Oakland Major League Baseball. Last week, the A’s gave their fans a fitting send-off to their time in Oakland with one more victory for its fans. The team beat the Texas Rangers Sept. 26, 3-2, giving Oakland fans a bittersweet moment of one final victory.

To understand the history of the team, you must know the history of the team. For these purposes, the story of the team will be divided into four parts, each aptly titled for what happened during that time period. As with many stories, it is long and complicated.

To understand why the A’s ended up in Oakland in the first place, one must understand the reasons why. The Oakland A’s were originally the Philadelphia Athletics, and were founded in 1901 in the newly created American League. The A’s original owner of the team was a man named Connie Mack, who was a former first baseman for the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Washington Nationals (no relation to the current iteration of the Washington Nationals). Mack was a good friend with Ban Johnson, whom he knew from his days as a baseball player.

This was a time when baseball was completely different from what it is today. Pitching was king and home runs were rare, free agency was non-existent, and the major leagues were segregated. This was a time when players such as Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Frank Chance, Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, Cy Young, Honus Wagner, Ed Walsh, and Addie Joss. The pitchers of the era, such as Walter Johnson, Cy Young, Ed Walsh, Rube Waddell, Christy Mathewson, among others, set many modern day baseball records for pitching, records that will probably not be touched.

Connie Mack had a shrewd mind and knew plenty about baseball. His team immediately saw success, with six AL championships in the first 15 years of the team’s existence. He quickly bought what many call the best team money could buy, which led to three title wins in four years, from 1910-1914. The team included Stuffy Mcinnis, Eddie Collins, Jack Barry, and third baseman Frank “Home Run” Baker, who hit a grand total of 96 home runs in his career. On top of that, they had pitchers Chief Bender and Eddie Plank, both dominant pitchers as well.

Unfortunately, the good times didn’t last. In 1914, a new, third major league formed, the Federal League. Mack, who was unwilling to give in to the demands of his players, sold them off in short order for nothing but cash. The team went into a spiral, going from pennant winners to basement dwellers, going from winning 99 games to 43 games in one year. The next year, they would outdo themselves again, winning only 36 games and losing 117 games. It would be another 10 years until the A’s would be contenders for a pennant.

Until then, for six straight years, the A’s would finish last in the American League. However, the team slowly rebuilt and by the end of the Roaring Twenties, Mack had built a contender once again.

Most fans will connect the 1920s to the Babe Ruth-led Yankees of the decade. However, many will forget that the A’s won back to back to back American League titles, from 1929-1931. The team that accomplished this is considered some of the most dominant teams in baseball history. The team was populated by players who were superstars, but are almost forgotten today except in the memories for those who watched him.

Jimmie Foxx was the cornerstone of the franchise during that time. In 1932, he nearly broke The Babe’s single season record for home runs, one that Ruth claimed that no one would ever break. He had massive biceps, and long, broad shoulders. He swung a 37 ounce bat and made a specialty of whacking massive home runs. Along with that, he was a stellar third baseman as well.

Aloyuis Simmons, known as Al Simmons, was the son of a carpenter from the Bronx. He was a great player in his own right, and was arguably at his peak during the time. He was a great outfielder and a great power hitter.

Mickey Cochrane, was the catcher of the A’s. He was a very good hitter, but was well known for his fiery temper and an indomitable spirit for the team. He was a very good defensive catcher as well.

Not to be outdone, the pitching staff of the A’s was also very good. Robert “Lefty” Grove was the team’s ace. He was arguably the most dominant pitcher in baseball at the time, and also was an MVP in 1929. George Earnshaw was also a very good pitcher who had a nasty curveball.

Eventually, hard times would once again hit the A’s. The Great Depression hit the A’s harder than most teams, and eventually, Mack was forced to sell his stars for hard cash. He sold his stars one by one and the money received kept the team afloat during the Great Depression. This caused the team to once again nosedive towards the basement of the American League, where they would stay for most of the time they stayed in Philadelphia. For the next 19 years, the team would dwell in the basement of the American League, finishing in the bottom of the league 16 out of the 19 years they spent in Philadelphia.

It didn’t help that as Mack got older, he became more and more of a penny pincher. Shibe Park became more and more outdated as the years went by, and Mack was unwilling to put money into the stadium. Mack passed away in 1956 at the age of 93.

In 1950, Mack stepped down as manager of the A’s, and then slowly stepped away from day to day operations of the team. Meanwhile, his sons were quickly proving themselves to be incompetent, and for a while, the Commissioner of Baseball, Ford Frick, considered having the league take over the team.

Eventually, in 1955, Mack’s sons sold the team to Arnold Johnson, a Chicago real estate mogul, who then promptly relocated the team to Kansas City. The team still had trouble, as the team still was terrible. The highest finish the A’s had in Kansas City was a sixth place finish in 1955, the same year the team moved to Kansas City from Philadelphia. It quickly became clear that Johnson only cared about making money off of the team, and the players were sold off in quick succession when they became good enough to command a good salary, including Ralph Terry, Whitey Herzog, and Roger Maris (If that last name rings a bell, it’s because he was the man who broke Babe’s single season home run record, the year after being traded to the Yankees.) to the Yankees in what were often one-sided trades.

In 1960, during spring training, Arnold Johnson dropped dead from a stroke. His estate took over the day-to-day running of the team until a suitable buyer could be found. The lucky fellow who bought the team was Charles Finley. Finley was a medical insurance executive in Gary, Indiana, and was quite a showman. Attendance was declining in Kansas City. Finley hated Kansas City, and began talks with the city governments of Louisville, San Diego, Oakland, New Orleans, Seattle, and Milwaukee. In January 1968, Finley announced that the team was moving to Oakland.

Finley decided that he would start spending money and scouting the country for players who would fit his team. The scouts he recruited were actually good at their jobs, and they found some talent. Some of the players he found included Reggie Jackson, Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Vida Blue, Rollie Fingers, Rickey Henderson, and Tony La Russa. Five of the six players mentioned were Hall Of Famers. It came to no one’s surprise that the A’s won 5 straight division titles from 1971 to 1975, and three consecutive World Series titles from 1972 to 1974. The team was at its peak at this time, with talent all throughout the roster.

However, Finley was, like many owners, faced with a dilemma. The players he was able to sign for very little at the beginning of their careers believed (and rightfully so) that they deserved to be paid more than what they were making. The Great Oakland Fire Sale started auspiciously enough, with Jim Hunter allowed to walk, going to the Yankees as a free agent. Within several years, the team was forced to sell or let go of all their stars, excluding Vida Blue (who was traded in 1977, and then plead guilty in 1981 of selling crack), all but dismantling the A’s lineup. Blue was also low-balled and resented Finley, reportedly saying in 1976, “I hope the next breath Charlie Finley takes is his last. I hope he falls flat on his face and dies of Polio.”

The team rebounded, with new talent such as Jose Canseco, Mark McGuire, Walt Weiss, Dennis Ecklersey, and Dave Stewart. The team went to three straight World Series, winning one in 1989, after the infamous earthquake hit San Francisco. By this time, however, Finley had sold the team to Walter Haas, who had rebuilt a winner in Oakland. However, after 1989, success was far in between. Haas died in 1995, and the team was sold to Steve Schott, who then brought in General Manager of the A’s Billy Beane. Over the next two decades, the A’s would rewrite how to run a baseball team and change the course of baseball forever.

Billy Beane was a figure who transformed the game of baseball for all time. He used analytics to decide whether to take a chance on talent that otherwise would have been overlooked. This strategy worked immediately, as the A’s would take talent and turn the team into a perennial contender in the American League West.

With players such as Barry Zito, Tim Hudson, and Mark Mulder, known as the big three, the A’s would make the playoffs in four consecutive years. Beane became known as a genius in scouting talent and would make trades that at the time to many seemed bizarre, but would end up working out for the team. Beane did this while sporting the lowest payroll in baseball, spending only $42 million and winning 102 games in 2002. The idea was not to trade away players when they asked for higher salaries, but to get guys that are overlooked and make the team better.

This changed the way teams thought about talent, with teams now considering the stats of on base percentage and strikeout-walk ratio as well as the conventional stats. However, this era would see the A’s win a world series title. The team would eventually begin to struggle, and this would spell the end of Oakland baseball.

Eventually, teams caught on to the A’s success, and began to implement the lessons that they learned from moneyball, which eventually took away what edge the A’s had in their division. The team eventually went from the principles of moneyball to just a rotating door of players getting shipped off when they would command higher salaries. By 2012, all the faces of moneyball, except Billy Beane, who was promoted within the team, were gone. However, in the two years following, it seemed that the team was close to breaking into the upper echelon of baseball, as they would come close to moving on to the American League Championship Series, before bowing out both times to the Detroit Tigers. In 2015, they began yet another rebuild, and produced results quickly; however, hard financial times would hit the A’s because of John Fisher.

John Fisher was the new owner who took over the team, and he was a penny pincher. He took numerous short-cuts to make money, including covering up six sections of upper-tier seats in center-field of the Oakland Coliseum. The fans stayed away because Oakland is notorious for its slums, and the fact that the team’s ballpark was in sketchy neighborhoods that most people tried to avoid at all costs. The stadium was beginning to fall apart from disrepair as Fisher was in the middle of a dispute with the city of Oakland over a new proposal to build a stadium on top of a run-down project. With neither side budging, the team asked permission to seek relocation, which was granted by the MLB in 2021. Fisher then sold off all of the players that he could for basically nothing. In 2023, it was announced that the A’s would be moving to Las Vegas. The fans protested strongly, and it seemed that the talks to build a new stadium in Las Vegas stalled. Eventually, it was announced that they would play in Sacramento from 2025 until 2027, and then move to Las Vegas in 2028.

It is clear that both John Fisher and the city of Oakland are responsible for the A’s leaving Oakland. The city could have compromised to get the new stadium to John Fisher, and Fisher could have also offered to foot some of the bill to build the stadium. It is a shame for the A’s fans in Oakland, who no longer have a team to root for. This was something that should have been solved, but due to saber rattling, it was not. And so the team’s future is now in limbo because of it.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Fuquay-Varina High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.